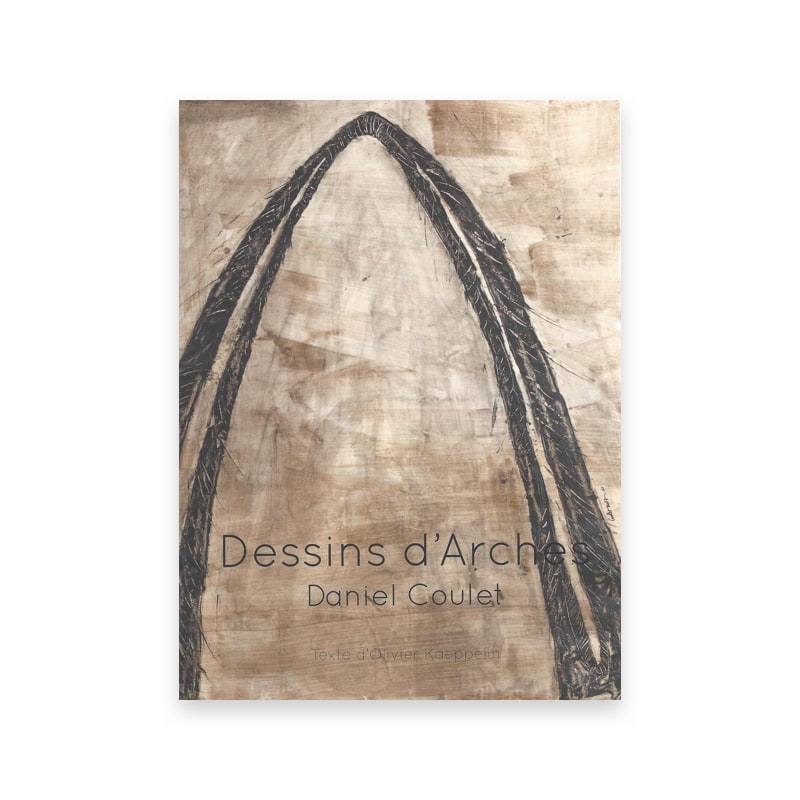

Les Arches de Daniel Coulet, Dessins d’Arches

Olivier Kaeppelin

Les Rencontres d’Art Contemporain Editions, Cahors, 2019

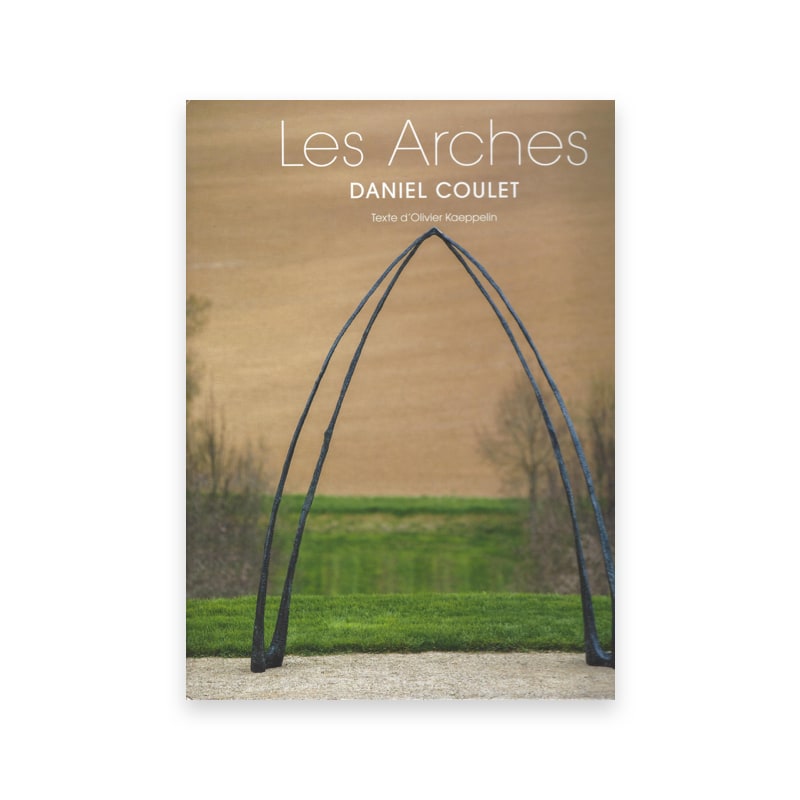

Les Arches de Daniel Coulet

Olivier Kaeppelin

Somogy, Paris, 2017

The Mysterious Accolades

“I discovered Daniel Coulet’s first arch in a garden in Toulouse, the Jardin des Abattoirs. If you go there, you will first observe a line in space. The sculpture seems light, the top of its curve blends with the blue of the sky. It generates an elevation, but that elevation is dependent on one’s gaze. If I face my body toward the bronze of the work and pass through its form, I am drawn in by a tension, a distortion which disrupts the balance and which, through the movement, forces me to become aware of the instability of my position and my basis.

I am no longer that man, lifting my eyes to the light, but a walker reminded by the sculpture of our ambivalent nature, between the ground and the air, accentuated by how the arch’s feet widen, by the patina’s state that presents us with a confusing animal kingdom, a strange skin like monsters or chimeras. Daniel Coulet’s arches are profoundly physical. They are bodies whose origin we cannot specify.

If they accept the heritage of scholastic thought and the longing for light, they understand it without forgetting the flesh, the substance that binds us to the ground.

They never abandon the fragility of their upright position and the suffering that humanity experiences in imagining its uprooting from gravity. His arches do not play with the illusion of an ascension. On the contrary, they underline the complex intertwining of matter and spirit.

If there is a “chimera”, the one before me is made of the immaterial, “bodies without bodies”, and impressive creatures from the mists of time. The arch unites opposites here. Its kingdoms, its rhythms generate “monster forms” similar to those of poetry. When we pass under the arch, aren’t we drawn into an immense space larger than ourselves, like that of Jonah’s whale? The sculpture swallows us and envelops us in the volume it creates.

In this sense, the arch is a portal to the unknown, to another territory. Daniel Coulet’s sculptures are built through this act: crossing the threshold. Through their extension, they exert their influence on the emptiness that surrounds them both “before and after” the crossing.

They can be slender, fragile as a flexible and bent branch or, in contrast, tower like the gates of heaven or hell. Sometimes they carry tortured bodies which perhaps are those of the damned or, on the contrary, those who, after the apocalypse, freed from their weight, find new life. Sometimes they take on the appearance of shadowy and cruel divinities, of Cerberuses displaying at their gates the heads of those who have not been able to reach the universe “beyond”.

These sculptures stand upright, welcoming or hostile. They allow the ambiguous experience of space, of its reciprocities. In doing so they create a scene where we are led to the boundary’s edge to take “the step beyond”. There exists a backwards and forwards, past and future, day and night, suffering and joy. We are the subjects of these dual architectures that dominate us.

Their way of life forces us to revolve around their construction. It imposes a definition on us, one echoing this static structure that fixes us to its immobility.

This unique arch position is only one of the possible manifestations of its existence. It is a starting point that has been enriched by duplication, twinning, and multiplication linking one arch to another like the fantasy of a cloister, abbey, or palace. In this way they can enclose us for a time in their volume or, in contrast, through the air that circulates between them, to create a scansion that invites the walker to progress. Light is no longer a source, nor a star to reach, nor a mystery to discover “behind the mirror”. It now plays with the shadows of the voids and solidness that the arches generate. It is no longer a question of crossing, but of steps, a path, a passage. The below and the beyond disappear in favor of a shifting that transforms the one who completes it. The experience is no longer the experience of a revelation but of a metamorphosis.

I picture that walking under those arches is like walking through a clearing. More abstractly, I experience a process of being altered. At that moment, the “actor of the arches” becomes the “one who passes through”. In motion and through motion, he will renew himself. These sculptures suggest a space of initiation, that is to say a space where the play of values, continuities, shifts, ruptures, and variations transform the one who is engaged in it.

From this point on, there is no longer totality or duality between opposing totalities sublimating or overwhelming us, but the extension of a movement. The moment full of the rush is our new totality but, this time, a totality that we know is elusive. We know it because architecture has now made us mobile. I remember writing in a poem, thinking of James Joyce, these words that translate this city walker’s metamorphosis:

“Arch upon Arch

the quays, the hotels

But empty is the stone up to

the anechoic chamber

consumed by words”

The man in this poem crosses a city at night and these steps of “Arch upon Arch” change him. The man in this poem, like the actor in Daniel Coulet’s sculptures, is nothing but for the light of a shifting that animates and defines him. He becomes the “one who passes through” that I mentioned. The passage allows him, by his progress, to change, to change his body, mind, life. This poetic expression of passage runs through all of Daniel Coulet’s work, in his sculptures as well as in his excellent paintings where a population of angels, people, and animals cross forests, burning spaces, to venture into the territory of painting itself. There is no longer a beginning or an end, but a state of transmutation, perhaps of transformation, in which “Arch upon Arch”, the shifting sweeps us along. It is these forms, these words – “Arch upon Arch” – that set the rhythm. They call forth the flow of Daniel Coulet’s sculptures. Door, passage, flow, these words give all their meaning to his works. They provoke the tilting, a dialogue between up and down, where directions constantly change. “Arch upon Arch” then produces the feeling of a permanent potentiality. It is at this moment that the axial principles of sculpture are reversed and where I used to see an arch, I now see a hull, a boat. I no longer look up between a portal and a choir. The elevation disappears, revealing in this way the presence of another nave. The space capsizes from top to bottom, this nave navigates on the water’s surface. The house has become a boat. The acute angle of the roof turns on itself. The inverted arch goes into the water. The sculptures lead us into a gyration that defines the very singular nature of Daniel Coulet’s works. He no longer constructs a sculpture in the classic way or nor does he ground it, as Carl Andre wished, but creates a plastic space whose principle is this gyration. Daniel Coulet thus proposes to cross, to elevate, but at the same time to return, to “navigate” and so to inhabit, through this double state, the volumes he creates. He seizes the arcades and the arcatures. Thanks to them, he creates a space that is at once architecture, a body, a heart, a path, and pure movement. In our mind’s eye, it conjures up sensation and spirituality in a mobile and almost cinematographic way.

In this sense, he follows Auguste Rodin’s recommendations given in his interviews with Paul Gsell as closely as possible.

“(…) Strengthen within you the sense of depth. It is difficult for the mind to become familiar with this notion. The mind is only able to clearly see surfaces. Imagining the thickness of shapes is not easy for it. Yet this is our task.”

“(…) All life emerges from a center and then germinates and blossoms from within and without” and again “…the great point is to be moved, to love, to hope, to tremble, to live. To be a man before being an artist! True eloquence makes a mockery of eloquence,” said Pascal. “True art mocks art (…).”

Daniel Coulet couldn’t care less about art as a mere formal arrangement. His work on arches is by no means a theme to be illustrated or a project to be executed. It only develops, enriches, and varies to suit his deep knowledge and current experience of these forms: arcs, arches, arcades. If he is freely inspired by certain architectural principles, he creates, above all, a hitherto unseen territory of his own, whose poetic expression allows access to a cosmogony whose vanishing points, perspectives, are above all interior – in a way, a vernacular cosmogony.

Walking along the paths these arches arrange or project, becoming their “rail worker”, elicits a rare and ambivalent feeling. That of a land to which we are anchored, of which we are day laborers. We know its weight, its design, its lines. Even so, it’s not a matter of being the surveyors but of being the visionaries. From the sculptor’s heart, his hand, this vision unfolds. It takes hold of us for a universe where the word surveyor is replaced by that of weightlessness. Daniel Coulet sculpts this weightlessness.”

Olivier Kaeppelin

Interview of Daniel Coulet by Olivier Kaeppelin

Olivier Kaeppelin: How did you conceive of and design your first arch?

Daniel Coulet: As a young sculptor I did not want, perhaps out of instinct, to fit in with what I saw in museums and art galleries, or what I read in magazines. It wasn’t a question of pretension but of sincerity. I didn’t recognize myself there.

How to create? How to express oneself sincerely in one’s own universe? What is quickly referred to as one’s style? Firstly, I wanted to dislocate volume in space by simple sculpting, and secondly, I crisscrossed it with rigid metal axes so it would become aerial and translate the verticality I was looking for. In this way I was able to satisfy both my desire to sculpt using the material I was looking for and my intention of a spiritual elevation.

I noticed then that by crossing these two desires, arches were revealed!

What is the most important thing you keep in mind in your arches: the shape, the symbol, the rhythm, or the line? How do you live or understand these different dimensions?

My arches have a visual efficiency that comes from the strength of “solid” sculpting, born from a movement, a torsion, Rodin spoke very well about that. This movement generates form, line, and surface at the same time. That’s why it is so difficult to achieve. The symbolism that comes out of it depends not on me, but on the reading of those who look at the arch. It is certainly a form rich in meaning and connections, whose meaning does not belong to me. The form creates the meaning.

Can we say that these arches are a door, a path, or even a “passage”?

Everyone defines things based on their own experience. The idea of rising and passage is very present in my studio. I also call some of my arches “doors”.

Do you make a connection between your plastic forms and certain religious cultures through a theme or a type of architecture?

In order to understand sculpture’s evolution, I had to discover the masterpieces of the past in churches, cloisters, and convents throughout Europe and beyond. These sources do show their influence on my work.

However, while it has a spiritual dimension, my work is not de facto religious. I do not deny that my creations may, at times, concern the sacred. A sacred, for example, that opposes the triviality of commerce or communication. It is what puts objects and ideas “elsewhere” and, no doubt, above our ordinary condition. Where? I don’t personally know.

How do you see your sculptures in relation to modern and contemporary sculpture?

My arches are, of course, directly related to modern and contemporary sculpture. Compared to certain currents of this period, the big difference is that I do not work from an idea or a concept that my sculpture would illustrate. Moreover, I believe that my work asserts itself along the spectrum of the history of sculpture.

It is totally innovative because it shakes up tradition, but I don’t forget the legacy of Western sculptors.

For example, I think that knowing the work of sculpture on the body at the beginning and end of the 13th century helped me in the creation of certain arches, as much as knowing sculptures by Rodin, De Kooning, Germaine Richier, Toni Grand, and a few others did. It is on the strength of these sources that I, in shaping the clay, for example, let the spiritual and original substance of my work “appear”.

For you, what is a work made for a public space? I’ve just mentioned the religious framework but you’ve also created works for other types of spaces, a garden or the Metro… How do you envisage the relationship of your work to these spaces or to the concept of a monument?

My work is about questioning the sacred. In fact, most of art history revolves around this dimension, even in the form of sacrilege or irony!

This sacred is not religious, nor does it touch the “new age” dimension that clutters our mentalities. My works are generally placed in sites chosen by the sponsors (gardens and public squares, subway stations). I’m first in dialogue with engineers and landscape designers before my work is seen by the general public. The latter does not always want to see art and often doesn’t have the cultural Rosetta Stone to understand it. It is therefore necessary to find the “lowest common denominator”, but without ever disavowing what we’ve done! We must always continue to talk about surpassing ourselves, especially in regard to those who are struggling to survive and have a better life! I believe that this way I have more respect for my fellow humans. The more difficult life is, the more essential it is to allow a glimpse of light in, through evocation, through perceptible knowledge…

Can you talk about the materials you use, from synthetic materials (epoxy, resin) to materials such as bronze or aluminum?

There are two very distinct types of materials in my work.

1– I model the sculpture with specific clays, clay mineral-based, other various “modeling clays”… Depending on the fluidity of these materials, the sculpture comes to life through different consistencies, with a modified appearance. The clay offers an infinite variety of modeling possibilities. What starts as a very simple initial application can be used to create complex solutions. I need a material that imprints impetus, movements, and occasionally the upward properties of volume.

2– Once the original sculpture is finished, I cast the pieces in bronze, aluminum, or composites (exclusively for interior parts). The relationship each of these materials has to light informs my choice. Bronze has a very particular relationship to light that is suitable for arches. It absorbs light. Aluminum, on the other hand, reflects this light. I play with that. These two materials develop different semantics.

Your imagination takes root in your country. You love its nature, its culture, its art, its churches.

There’s a type of osmosis between me and the Mediterranean scrub and the garrigues of Nîmes regions and the north of Montpellier. I came into contact with Roman sculpture at a very early age and I know the amphitheater in Nîmes by heart. Moreover, I still take walks in the Mediterranean scrub. The Romanesque pearl of Saint-Martin-de-Londres and the Priory of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert serve as a resting point.

I am steeped in these origins without being able to say exactly if this piece or the other results from this influence.

Your work is above all a question of form and space, much more than one of images and objects. Does the cognitive and sensory experience that you offer include the ambition to share a universal experience?

Yes, absolutely, that’s the essence of my work and my thinking…

How to make those who look and those who will look at these works feel and understand this sharing, which I describe as “adogmatic”! Emotion and the sacred unite, while religions and ascribed truths divide, alas, by their dogmas! To avoid what René Char called “times of inclemency”, I try to express this possible sharing in my sculptures while avoiding the expression of a supermarket spirituality or a strategy of commercial reproduction or even a sterile, kitschy copy of a supposed artistic golden age. Through my works, I try to offer a path that I hope is both individual and collective.

Ludwig Museum, 1992-2012, 20 Jahre

Beate Reifenscheid

Heinrich Koblenz, 2012

“Der in Paris und Toulouse ansässige Bildhauer und Maler Daniel Coulet (geb. in Montpellier 1954) gilt als einer der aufstrebenden Künstler der französischen Kunstszene. Vor allem größere Monumentalskulpturen, die Daniel Coulet in den vergangenen Jahren im öffentlichen Raum platzieren konnte, weisen ihn als einen Meister der Skulptur aus (Projekte in der U-Bahn in Toulouse, im Skulpturengarten des Musée d’Art Contemporain in Toulouse etc.).

Daniel Coulet arbeitet darüber hinaus als Maler und Zeichner. Hier nutzt er vornehmlich chinesische Tusche, deren Schwärze er bevorzugt, um seinen Darstellungen eine nahezu mystische Tiefe und Unruhe zu verleihen. In seinen Bildwerken vermag er es, in die Tiefen menschlicher Abgründe hinab zu steigen. Er entwickelt gleichsam im Fluss aus Farben (indem er das Schwarz bis in helle Grautöne modelliert und gelegentlich Weißhöhungen einbezieht, wie er auch rote Tusche zur Steigerung der Emotionen verwendet), der seinerseits ein Szenario aus Märchen, Albträumen und Höllenvisionen evoziert. Coulet rekurriert dabei scheinbar auch auf bedeutende Vorbilder wie Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), dessen Porte de l´Enfer (Höllentor, 1885) er ebenso ikonografisch wie stilistisch für seine monumentalen Tore nutzt als auch die schlanken Gestalten und Torsi bei Alberto Giacometti oder die aufgeladene expressive Stimmung im Werk von Edvard Munch (z.B. in „Der Schrei“ von 1905). Entscheidend ist für das Verständnis seines Werkes jedoch nicht die Adaption des fremden Werkes, sondern die eigene Sprache und Formulierung in der Skulptur und der Malerei, die Coulet längst gefunden hat. Mehr noch als in der Zeichnung setzt er sich in der Skulptur mit den Gesetzen der Architektur auseinander, löst Flächen in nahezu filigrane Verstrebungen und Verästelungen auf. Die Form entwickelt er immer aus der Linie heraus.

Die Präsentation im Ludwig Museum wird die erste Einzelausstellung des Künstlers in Deutschland sein. Als Partner der Ausstellung konnte des Musée Paul Dupuy in Toulouse gewonnen werden, das hauptsächlich das zeichnerische Werk von Coulet vorstellen wird, während im Ludwig Museum die großformatigen Zeichnungen mit den Skulpturenmodellen und den großen, in Bronze ausgeführten Skulpturen in einen Dialog treten werden. Bei den Modellen verwendet Daniel Coulet als sehr eigenwilligen, jedoch höchst anschaulichen Werkstoff einen speziellen Kunstharz (resin) an, der ihm alle Größen in der Ausführung bei gleichzeitiger Wahrung der Details erlaubt. Vorgesehen sind eine größere Gruppe an neueren Skulpturen im Ludwig Museum sowie zwei große Skulpturen im Außenbereich des Ludwig Museum sowie – ebenfalls in Kooperation – die Präsentation eines großen Retabel (Altarbild, ca. 4,50 m x 6 m) in der angrenzenden St. Kastor Kirche, das Daniel Coulet eigens angefertigt hat. Großformatige Bilder (Zeichnungen auf Leinwand und auf Reispapier) akzentuieren die motivischen Themen von Coulet, ohne sich als Vorstudien zu den Skulpturen zu verstehen.

Die Ausstellung wird unterstützt von der Stiftung Rheinland-Pfalz für Kunst und Kultur sowie vom Ministère de la Culture de France in Paris. Sie entsteht in enger Zusammenarbeit mit dem Künstler zum einen und mit dem Musée Paul Depuy in Toulouse zum anderen. Zur Ausstellung entsteht ein Katalog (frz./deutsch) bei Silvana Editoriale.”

Dr. Beate Reifenscheid

Koblenz, le 12 janvier 2010

Tram

Friedmann, Pencreac’h, Coulet, Fauguet

Olivier Kaeppelin

Éditions Privat, Toulouse, 2011

“Daniel Coulet’s work is that of a visionary. The forms he sculpts refer to fragments of reality that we know, human bodies, flowers, horse heads, arches, but captured by a movement, a twist, an abstraction in such a way that they reveal the artist’s purpose: to express an internal space, built by the obsession with light, matter, nature carried away by the “phenomena” that transform them. These can be named, for one thing. They are sometimes bearers of tragedy: fires, flights, storms, darkness, just as they can also mean exaltation, elevation, joy.

Daniel Coulet’s works are built on this paradox, this contradiction that gives them a theatrical dimension. They do not draw on the images of their time but, like some contemporary Chinese works, use ancient images or representations that have their origins in legendary texts: the Bible, the Odyssey, the Holy Grail, and the Knights of the Round Table, or, closer to home, William Shakespeare, Ezra Pound, or Ted Hughes. The bet is that these forms, which have traveled through time, will run more in parallel with our lives than the figures of the present day. In this sense I understand the horse’s recurring presence through the parts of its body – head, spine or, as we see here in Toulouse: hoof, muscles, leg. Sculpture, which, depending on the angle, can appear abstract or figurative, is a challenge, an affirmation of energy, a break in the city’s universe which, by definition, is one of codes, rules and grammars. In this sculpture, there is therefore a Don Quixote-like or even more of an Arthurian attitude, when Arthur tells Jaufré that it is time to ready the horses to go on an adventure, since adventures do not come to the court, or, one might also say, come to the law, civilization, the city. In its deceptive aspects of classical composition, this work is a rebellious work, in the way that Pier Paolo Pasolini evokes when he states that we must believe in “the extraordinary revolutionary force of the past”, a past which, through its resurgence at the heart of the present’s “worldliness”, questions and criticizes its convention, but even more so becomes an active force to give life back to the universe, thanks to a deeper awareness of time. In the manner of Bartabas or Pierre Guyotat, this celebration of an ancient form and substance, appearing and disappearing in the sun’s reflection on cast aluminum, is a call, as we leave the offices of the busy city, to experience within us at every moment the hypothesis of an imagined city, of a new life.”

« Si che chiaro Per essa scenda della mente il fiume. » Dante, Purgatory, Verse 89, Canto 13

Olivier Kaeppelin Excerpt from La ligne du Tram et la route de Grenade

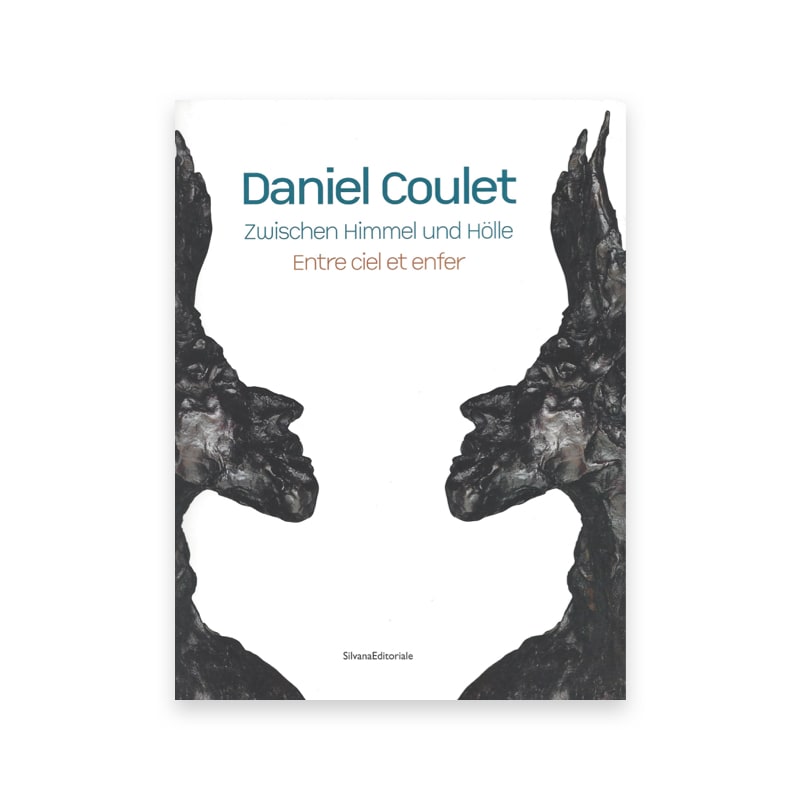

Daniel Coulet, entre ciel et enfer [Zwischen Himmel und Hölle], Ludwig Museum

Beate Reinfenscheid, Jean Penent

éd. bilingue, Silvana Editoriale, Milan, 2010

Shadow and Light, Daniel Coulet

“…The Order and the Ministry of Culture commissioned Daniel Coulet, along with the master glazier Jean-Dominique Fleury, to recreate the stained glass windows of the Notre-Dame d’Aubin church (in Aveyron). It is probably due in particular to Daniel Coulet’s innovative reinterpretation of the raw material – glass – and his individual approach to the two proposed subjects (La vie de Sainte Emilie de Rodat [The Life of Saint Emilie de Rodat] and Le père Marie-Eugène de l’Enfant-Jésus [Father Marie-Eugène de l’Enfant-Jésus], a high-ranking Carmelite official), that the church has become a magnet for believers and tourists alike. In this context, it may also appear significant that, not far from there, just a few years earlier, Pierre Soulages had been commissioned to create the stained glass windows of the Abbey Church of Sainte-Foy in Conques. Originally from Rodez, the artist completed a total of 95 glass windows in the abbey church, which with a milky opaque glass with black stripes create a very special lighting scheme in the church. Despite the many formal differences between the two works, one cannot fail to consider not only the two churches’ geographical proximity, but also the high artistic bar set by Pierre Soulages, to be a true challenge for Daniel Coulet. With their own personal artistic expressions, both artists have succeeded in releasing something in the viewer’s perception that can be equated to a deep spiritual experience; one uses a totally abstract approach, the other the forms of narrative and traditional, albeit reanimated, iconography. In this work, Daniel Coulet proves that he possesses an iconographic vocabulary reminiscent of the old masters, without abandoning the new accents and interpretations typical of his visual style. In sum, we find almost his entire pictorial repertoire here, the set of figures and details that he uses and alters over and over again.

What Daniel Coulet creates are nothing more than shadowy entities reduced to the line. At the same time – and this is the greatness of his artistic method – the line becomes architecture and awakens the image of Gothic cathedrals in the observer’s mind. Line and shadow become monument… The most lasting impression Daniel Coulet’s sculptures leave is their monumentality, the degree of their aspiration to rise and “grow beyond themselves”, characteristics that give them something majestic. In this way, Coulet sometimes reconciles the drifting apart of man and nature, bridges that expanse by reconnecting to nature and by orienting all earthly things (and being oriented) toward the light, toward God…”

Beate Reifenscheid

Excerpts from the text Shadow and Light, Daniel Coulet, ed. Silvana Editoriale, Milan – Ludwig Museum Koblenz 2010

Schatten und Licht, Daniel Coulet

“…Der Orden und das Kulturministerium beauftragten Daniel Coulet gemeinsam mit dem Glaser-Meister Jean-Dominique Fleury, die Kirchenfenster von Notre-Dame d’Aubin in Aveyron neu zu erschaffen. Es liegt wohl insbesondere an Daniel Coulets neuer Interpretation des Materials Fensterglas sowie seiner individuellen Auseinandersetzung mit den beiden gestellten Themen (La vie de Sainte Emilie de Rodat und Le Père Marie-Eugène de l’Enfant-Jésus, hochrangiger Amtsinhaber des Karmeliterordens)), dass die Kirche seitdem zu einem neuen Anziehungspunkt für Gläubige und Touristen geworden ist. Es mag in diesem Zusammenhang bedeutsam sein, dass, nicht weit entfernt davon, wenige Jahre zuvor Pierre Soulages in seiner ehemaligen Heimatstadt Rodez den Auftrag erhalten hatte, die Fenster der Abteikirche von Sainte-Foy de Conques zu gestalten. Insgesamt vollendete er dort 95 Fenster, in denen er mit einem milchig-opaken Glas und schwarzen Streifen eine ganz eigene Lichtregie für die Kirche entwickelte. Man wird trotz aller formaler Unterschiede nicht umhinkönnen, nicht nur die geografische Nähe der beiden Kirchen als eine Herausforderung für Daniel Coulet zu begreifen, sondern auch die von Pierre Soulages künstlerisch vorgelegte hohe „Messlatte“. Beiden ist es gelungen, mit ihrer ganz eigenen künstlerischen Ausdrucksweise etwas in der Anschauung durch den Betrachter freizusetzen, das sich mit tiefer Spiritualität in Verbindung bringen lässt. Der eine auf eine vollkommen abstrakte Weise, der andere mit den Formen der Narration und der traditionellen, wenngleich neu beseelten Ikonografie.

Hier nun entfaltet Coulet ein ikonografisches Vokabular, das an die alten Meister erinnern lässt, ohne dass er auf neue, für seinen malerischen Duktus typische Akzente und Interpretationen verzichten würde. In der Summe findet sich hier nahezu sein gesamtes malerisches Repertoire mit den Figuren und Details, die er immer wieder verwendet und variiert… Was Daniel Coulet erschafft in seinen auf die Linie reduzierten Skulpturen, ist nichts anderes als Schattengebilde. Zugleich – und das macht die Größe seines künstlerischen Handels aus – wird die Linie zur Architektur und verlebendigt die Assoziation an gotische Kathedralbauten. Linie und Schatten werden Monument… Der nachhaltige Eindruck seiner Skulpturen orientiert sich jedoch an deren Monumentalität, an dem Grad ihres Aufstrebens und „über sich selbst Hinauswachsens“, der ihnen etwas Majestätisches verleiht. Dergestalt versöhnt Coulet zuweilen das Auseinanderdriften von Mensch und Natur, überbrückt die Entfremdung in der Rückbindung an die Natur und im Ausrichten (und Ausgerichtetsein) alles Irdischen auf das Licht, auf Gott…”

Beate Reifenscheid

Auszüge aus dem Text: „Schatten und Licht, Daniel Coulet“, Hrsg. Silvana Editoriale, Mailand, Ludwig Museum, Koblenz, 2010

Last Judgment, Flood and the like

“Coulet’s personal universe is body and soul with this territory of the Mediterranean Languedoc, where the grapevine fiercely competes with the scrub and the evergreen oak, where villages conceal forgotten treasures of Romanesque art, where every tree and every stone, the very earth, all evoke the most terrible of tragedies, the one that saw a civilization’s annihilation. One will therefore not be surprised by certain titles’ strangeness, calling up Jugement dernier dans un paysage [The Last Judgment in a Landscape] or Jugement dernier dans un sous-bois [The Last Judgment Day in an Undergrowth]… Terrible events – the Eternal Judge separating the chosen from the reprobates – are supposed to take place in majestic and peaceful places, havens of coolness in oppressive weather. We can guess at mysterious accusations and sentencings, with figures who mingle with the trees, become trees themselves. Sometimes a branch encircles one of them like a crown. The trees form arcades within which hieratic silhouettes, such as saints or angels from early Christian sarcophagi, are inscribed. Elsewhere, these elements become architectural to enshrine their theories of the chosen ones underneath round arches.

Unaffected by contemporary taste and fashion, Coulet never ceases to question the artists of a thousand years ago who fascinated him in his childhood and whom he still sees alive before him. His compositions, superimposing scenes and registers, unconciously evoke the tympanums of church portals (Treize personnages [Thirteen Figures], Deux anges traversant un déluge… [Two Angels Crossing a Flood…]), his processions of lintel ornaments, his solitary filiform figures, the slender saints of the overmantels and the door jambs. He intends to measure himself against the Master of Cabestany, whose famous sarcophagus Martyre de Saint Sernin [Martyrdom of Saint Sernin] adorns Saint-Hilaire-d’Aude’s modest church, and who he understands so well, as one artist to another. Not far from there, also in this privileged area, in Lagrasse, in Saint-Papoul and in Rieux-Minervois, this Romanesque artist, who was known from Tuscany to Navarre, is present in other works. Coulet pays homage to him with two large sculptures explicitly titled Portes pour le Maître de Cabestany, 1 et 2 [Doors for the Master of Cabestany, 1 and 2]. Another pivotal point for Daniel Coulet’s imagination is at Saint-Guilhèm-le-Désert. Here, the grandeur of medieval art is in harmony with the harshness of its environment, made up of sharp rocks, thorny bushes, and tormented trees that look as if they were hanged in the sky. In this sacred setting where the famous “William of Orange” withdrew from the world – some twenty chansons de geste, or epic poems, are dedicated to him – he placed two striding angels in the foreground, who seem seized by the splendor unfolding before them (0739). This “dramatic landscape” accompanies or introduces a series in which charred trees, juxtaposed against a blazing background, recall people’s silhouettes, sometimes mixed with those of horses. This ensemble, often represented by large-format paper marouflage compositions, is an innovation in the artist’s current output, which offers us subjects as unusual as L’homme à la bécasse [Man with Woodcock] (0747), Personnages, oiseaux et poissons [Figures, Birds, and Fish] (0751), or Voici qu’apparut à mes yeux une foule immense que nul ne pouvait dénombrer [Here a Huge Crowd Appeared Before My Eyes that No One Could Count] (0778). The spirituality emanating from Daniel Coulet’s works in the various fields of his creation – the exhibition presents a magnificent chapel design, simultaneously sculpture and architecture (6088) – has aroused interest among religious patrons. After the stained glass windows for the church of Notre-Dame d’Aubin (Aveyron), illustrating the Vie de sainte Emilie de Rodat [Life of Saint Emilie de Rodat], he created the entire decoration for the church in Bordes (Pyrénées-Atlantiques), where he combined painting and sculpture. He also presents before us the no less important Retable pour la basilique Saint-Castor de Coblence [Altarpiece for the Basilica of Saint Castor in Koblenz], the center of whose triptych features the Sermon du Christ sur la montagne [Christ’s Sermon on the Mount] and Le Déluge [The Flood] and La Source de vie [The Source of Life] on the side panels. The places suggested are always evocative of the arid hills and sparse trees of the Languedoc, mysteriously bound to life. Promising perspectives open up with the Paysage à l’arbre aux pendus [Landscape with Hanging Tree] (0807). And the figures are always running. They already seem far away.”

Jean Penent

Daniel Coulet, Les vitraux de l’église Notre-Dame d’Aubin

Pierre Cabanne

Éditions Un, deux, quatre, Clermont-Ferrand, 2004

“Black is neither night nor shadow; its matter holds the germs of the signs that will unfold, containing and giving life to wandering figures, specters, or chimeras, a whole people with a secret dream-bearing existence. To draw in black is to unite the visible and the invisible, the nightmare and the eve, expression and abstraction.

Black is a color that gives rise to impalpable shades or rays with multiple ranges of intensity, luminosity, or gravity; it is neither mourning, nor the cold sun and its chiaroscuro of twilights of melancholy or expectation. In the color black, painters have long sought a language of passion in its fullest freedom, the intense moment of a gesture or a cry, or perhaps a wound, whose emotional charge binds the mind and the hand. So it is with Daniel Coulet, sculptor and painter.

Sculpture is volume and gravity. It takes up a powerful place in space; writing the dark ring imprisons the form as both call upon light or are dependent on it. The light in the Midi can dazzle, drown things, plunge them into a blurred immateriality. Daniel Coulet’s India ink washes are not preparations for his sculptures, whose monumentality recalls the Romanesque churches of the South, at once slender and squat, products of the earth, momentum gathered up toward the sky. His works refuse effect, risky speculations, processes; the power inherent in their strangeness renders them tragic when they are simply true, conveying a graphic truth that is neither disturbing nor demonic. The painter may well be “inhabited”, but he does not work in that fever; the people of the Midi, a singular group, are in this way violently internalized, but stripped of confusion. The mystery is born of the everyday, of life. For Daniel Coulet, observation and imagination are one whole.

His inks do not explore the unconscious, but give an account of an inner world between the real and the fantastic, precision and allusion. It’s a world punctuated by the arches, ogives, and trees that come from his sculpture, which is also rooted in Romanesque symbolism. The person who designed the memorial, the bridge, and the altar in Rennes-Les-Bains, the ghostly trees of the Toulouse Metro, le Monument pour les oiseaux de Montségur [Monument for the Birds of Montségur], is working for the people, their everyday desires and needs; he is close to them, to their worries and their work…”

Excerpted from the text by Pierre Cabanne: The Stained Glass Windows of the Notre Dame d’Aubin Church, 2002, ed. One, Two… Four, Clermont-Ferrand.

Sculptures et encres de Chine

Pierre Cabanne

Catalogue d’exposition, musée des Beaux-Arts Denys Puech, Rodez, 1996

Sculptures and Works in India Ink

“Do the numerous users of the Toulouse Metro who pass through Mirail-Université Station and see L’Arbre fleur [Tree Flower] or La Fleur stalagmite [Stalagmite Flower], and their silhouettes running the length of the wall, think that this pair of works by Daniel Coulet contain the life pulsating in the heart and the soil of cities? The sap of organs that have neither time nor place, but carry both light and shadow, rumor and silence, in their abundant foliage. These trees give the meaning that Daniel Coulet imparts to his work, a boundless growth in which the city is the laboratory, where the sky stretches beyond the walls. Each sculpture sometimes contains another, as if grafted on, born of itself, which as it emerges surprises the eye and guides the hand while keeping the rhythm of the first.

Daniel Coulet is rooted in reality. He took his first forms from nature, from which he has made the lively and unceasingly recreated elements of his inspired repertoire. He has never detached himself from his rural origins. He was raised, he says, “far from everything”, and he lives today in the seclusion of endless horizon and sky; the paradox is that, despite this retreat, or more likely because of it, he never stops working for the people of the cities. The three monumental pieces he exhibits at the Rodez Museum – Monument pour les oiseaux de Montségur [Monument for the Birds of Montségur], Porte cendrée [Cinder Door], and L’Architecture en mouvement [Architecture in Motion] – prove it. These works, constructed from synthetic modeling clay atop support structures of wire mesh frames, whose bewitching originality strives to achieve the magical experience of a poem, contain traces of the fingers that grasped their rhythms and substance.

Not far from the “camp dels Cremats” in Montségur, this immense arch will stand, shouldered by a figure whose head is the keystone of the whole, with its trembling columns, those backbones that cross the space. It is the portico of tragedy, the propylaea of memory, the temple of time at the foot of the pog. In Daniel Coulet’s work, the gate’s symbolism is linked to the mystery of creation. In the piece entitled L’Architecture en movement, it is strange to see the forms mingle as they rise, becoming entangled with plant- or muscle-like structures, whose curvature and entwining, trapped by the sensory perception that created them, bear indisputable witness to the fusion of the natural world. All of Daniel Coulet’s sculptures, born of silence, meditation, and observation, are a testament to this: the human, the plant, and the animal have the same strength, the same evidence. Life is vulnerable, but it alone is capable of giving birth to the living. And the living, for him, is other people; it is for them, their everyday life, their enduring and fragile time on earth as humans, that he designed the memorial, the bridge, and the altar of the church at Rennes-les-Bains, the trees for the Toulouse Metro. It is for them that, with an incredible energy that shakes up lethargic bureaucracy, he plans sculptures for highway service areas, fountains, and numerous other projects that he has presented as far away as in China.

The small works, the arches and doors that he exhibits at the Rodez, express the same tensions, the same impetus, and the same appeals as in the monumental works. The artist needs people, and people regard themselves and find themselves in each other. Gone are the days when the artist puzzled and scandalized the public. The exchange is now one of collusion and complicity, and even more necessary. The sculptures are shared anchors in the city, visibly affirming a language that their collective passion justifies and understands.

The harsh light of the Midi Noir, different from the light of beaches or vacations, shaped Daniel Coulet’s way of looking; in his work we find rough, matte stones, grooved furrows, space that stretches the horizons to infinity. He is not the sculptor of the sun’s powerful rays, but of the shadows that lengthen at day’s end until they form the gigantic alphabet of a reconquered language. This Midi is ours, an identity that cannot be shared with just anyone.

The drawings in India ink wash, populated by arches and people, are the complement, his sculptures’ outlines in bold black lines, diluted stains, impasto, and drips; they are inseparable from one another. They contain the same deep, natural, inner revelation; they share with us anguish and fervor, reconciliation and turmoil. Le Jugement dernier [The Last Judgment], les Personnages dans la forêt [Figures in the Forest], or, in a landscape, les Personnages en mouvement [Figures in Motion], take shape and live in their urges of desire. “There can be no possible end, because as you get closer to what you see, you see more…”, Giacometti said to a friend. That’s why Daniel Coulet’s characters seem to be fleeing and pursuing others who are none other than themselves.

He, who lived with horses as a child, has sculpted a large, one-meter high horse’s hoof out of resin, which welcomes visitors to the Rodez Museum on the stair landing; I see it standing on the Lauragais plain like a sign of time rediscovered, a proclamation on this piece of land that is both calmed and burned, on which a destiny is drawn and affirmed.”

Pierre Cabanne

June 1996

Ed. Musée Denys Puech-Rodez

Bibliographie

2020

Christian Sabathié, La Grande Jambe de Cheval, Atelier, Paris

2019

Olivier Kaeppelin, Les Arches de Daniel Coulet, Dessins d’Arches, Les Rencontres d’Art Contemporain Editions, Cahors

2018

Jean Penent, Ce monde qui vient (préface), Château de Launaguet

Guy Claverie, Lecture(s) de la tradition, Château de Launaguet

2017

Olivier Kaeppelin, Les Arches de Daniel Coulet, Somogy, Paris

Guy Claverie , Les Arches etc…, Château de Laréole

2014

De l’art au design, du design à l’industrie, publication de la société d’éclairage public Ragni SAS, Cagnes-sur-Mer

2012

Beate Reifenscheid, Ludwig Museum, 1992-2012, 20 Jahre, Heinrich Koblenz, Coblence

2011

Olivier Kaeppelin, Tram, Friedmann, Pencreac’h, Coulet, Fauguet, éditions Privat, Toulouse

Toulouse, territoires du tramway, sous la direction de Robert Marconis, éditions Privat, Toulouse

2010

Beate Reifenscheid, Jean Penent, Pierre Cabane, Daniel Coulet, entre ciel et enfer [Zwischen Himmel und Hölle], Ludwig Museum, éd. bilingue, Silvana Editoriale, Milan

Daniel Coulet, zwischen Himmel und Hölle, in Kultur Info Koblenz

Daniel Coulet, zwischen Himmel und Hölle, in Top Magazine Koblenz

Coulet im Museum, in Rhein-Zeitung

Daniel Coulet, zwischen Himmel und Hölle, in Blick aktuell Koblenz

Neue Ausstellung im Museum, in Super Sonntag

Daniel Coulet, zwischen Himmel und Hölle, in Picture-Kulturspiegel

Daniel Coulet, zwischen Himmel und Hölle, in Wällerbote, 9. Jahrgang

Liselotte Sauer-Kaulbach, Daniel Coulet, zwischen Sintflut und Paradies, in Rhein-Zeitung

Kunst zwischen Himmel und Hölle, in Rhein-Zeitung

2009

Michèle Heng, Daniel Coulet revisite l’art sacré, in Atlantica N°165

2007

Pierre Cabanne, Daniel Coulet, Les vitraux de l’église Notre-Dame d’Aubin, éditions Un, deux, quatre, Clermont-Ferrand

2006

Mâts pour éclairage public, publication S. A. Petitjean, collection Contemporaine, Troyes

2005

Henri-François de Bayeux, Daniel Coulet, lavis des ombres, in Libération

Lydia Harambourg, Daniel Coulet, entre lumière et ténèbres, in Gazette de l’Hôtel Drouot N°16

Geneviève Breerette, Daniel Coulet, sombre vision, in Le Monde

Pierre Cabanne, Daniel Coulet, catalogue d’exposition, Galerie Libéral Bruant, Paris

1999

Jean Penent, Daniel Coulet, Les Cathèdres, cat. exposition, Les Olivétains, éditions CG31, Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges

1998

Serge Pey, Daniel Coulet, Tout Homme. Le Lampeur. Poème pour les hommes de Carmaux, encres de Daniel Coulet, Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations, Paris

Marc Alizart, Mille sept cent francs d’absolu, Galerie Eric Dupont

1996

Pierre Cabanne, Sculptures et encres de Chine, cat. exposition, musée des Beaux-Arts Denys Puech, Rodez

1995

Patrice Beghain, De Toulouse à Chongqing, cat. exposition musée des beaux arts de Chongqing, musée Paul-Dupuy, Toulouse

1994

Escultura de grandes dimensiones en el roser, Segre

Jordi Ubeba, Arquitectures estalagmitiques, in Nou Diari

Patrick Vandevoorde, Entretien, École des beaux-arts Lerida, Lerida (Catalogne)

1993

Christine Barbastre, Les Couleurs du métro, MT Développement, Toulouse

Christine Barbastre, Sculptures et dessins, cat. d’exposition, MT Développement Toulouse, coédité par la galerie Éric Dupont, Toulouse

Christine Desmoulins, Ticket de l’art dans la ville rose, in D’architecture

Martine Kis, L’art prend le métro, in Carnet de l’urbanisme, 1993

Pierre Rey, Quinze Artistes dans le métro, MT Développement, Toulouse

T. S., Métro : artistes en sous-sol, in Urbanisme

Intérieurs, cat. exposition, coédité par le musée des Beaux-Arts Denys-Puech (Rodez) et le musée Goya – Centre d’Art contemporain (Castres)

1992

Daniel Coulet, Nicolas Sanhes, Rolino Gaspari, Thierry Boyer, Entrée en matière, cat. d’exposition, Centre Bradford, Aussillon

Philippe Pujas, L’artiste appelé à servir la qualité de la ville, in La Tribune de l’Expansion

1991

Galerie Éric Dupont, Daniel Coulet, Toulouse, 1991

1990

Alain Mousseigne, Choix d’abstraits, musée d’Art moderne, Toulouse

Alain Mousseigne, in Ninety, numéro spécial Jeunes à suivre

1988

Patrice Beghain, Coulet, Le voyage de Jeanne, cat. d’exposition, éditions Arpap, Centre régional d’art contemporain Midi-Pyrénées, Labège

1987

Michel Servet, Patrimoine, art contemporain 87, Conseil général de l’Aude

1985

Alain Mousseigne, Daniel Coulet, Moments d’une démarche, Réfectoire des Jacobins, cat. d’exposition, Toulouse